Black Church Burnings:

The Outrage, Terror and Talk

of Fire

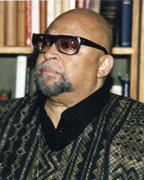

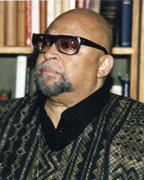

By Dr. Maulana Karenga

Discussing unspeakable acts of horror and revulsion is always

difficult. This is so not only because we often lack adequate words

to describe them, but also because we often lack a clear understanding

of their nature, motivation and meaning. The 18-month-long spate

of Black church burnings presents us with such a case and with

the painful and urgent challenge to define it and put a quick and

decisive end to it. An initial problem of discussion, after the

shock and outrage, is the difficulty of discussing the experiences

of people of color in appropriate and dignity-affirming terms in

a racially hierarchical society. Both the media and academy seem

unequipped to discuss the experiences and aspirations of people

of color in terms that would reflect an equality of status and

worthiness of equal regard. Thus, the ethical issues involved are

reduced to declarations of sorrow and distance from the acts; the

political issues to denying conspiracy and racial motivation; the

judicial issues to suspicion and investigations of the victims

and appropriate posturing in the legislatures and the social issues

to a few whites helping to rebuild a few physical structures rather

than the over-due need to confront a systemic racism which breeds

the worst of human thought and acts.

Acts of Racism

In spite of the tendency, and for some the need, to deny the racist aspect

of the burnings, this recognition is central to understanding them.

The burnings then are first of all acts of racism, as surely

as the burning of a synagogue would be considered an anti-Jewish act.

This is evidenced not only in the fact that virtually all the churches

burned are Black and virtually all those arrested in these cases are

white and in at least two cases in South Carolina those arrested are

linked to a white racist group, but also in the reality of a political

culture which is significantly defined by its history of racial domination.

In fact, the burning of African churches has a long genealogy in U.S.

history. From its inception, the independent African church which was

institutionalized in 1792 with the founding of the African Methodist

Episcopal Church came under attack. By 1829 in Cincinnati, the first

African church was burned. And these burnings continued through every

period in Black history-from the Holocaust of Enslavement through Reconstruction,

Jim Crow, and the Freedom Struggle of the 60's to the present. Beginning

first in the North, where "the visible" Black church first began and

then moving to the South after emancipation.

The arguments for a non-racial and non-racist motivation conveniently

forget that nothing comes into being by itself, that events always

unfold and acquire momentum and meaning in a definite context.

Thus, in the context of a racially punitive culture in which whites

are consistently taught to identify, condemn and despise Africans

and other people of color as a central, if not the fundamental,

source of their social and personal problems, one must rationally

expect racially motivated acts against them. Therefore, even the

white man who says he burned the Black church not out of racial

malice but personal anger at a Black man does not and cannot explain

why he burned the communal symbol and not a personal piece of the

Black man's property. And the young white girl claiming anti-religious

rather than racial motives for her burning, cannot explain how

and why she chose to burn a Black church rather than a white church

or white synagogue.

Even the talk of conspiracy or copy-cat burnings tends to hide

the systemic ground of racial motivation. Certainly, it would be

easier for the dominant society to discover and then distance itself

from a group of early-man types who unable to adjust to modern

moral life continue to practice social savagery. Then it could

keep its self-congratulatory illusion of having developed beyond

the social and personal pathology of racism. But even these early-man

types grow in a definite culture, as does the copy-cat arsonist.

Their ideas of the appropriate target do not drop from the sky.

They are a legacy and lesson from a society that devalues whole

peoples and assigns human worth and social status based on concepts

and illusions of race. It is this systemic origin of the burnings

that is the source of so much concern by African Americans and

an equal amount of denial by many whites. And it is this societal

denial that led to the artificial discovery of religious rather

than racial motivation and to the Justice Department's clumsy attempt

to use statistics before the period concerned to prove these burnings

have neither racial nor geographical boundaries.

Acts of Desecration

Secondly, within the overall context of racism, the burnings are also

clearly acts of desecration. They are a violation and destruction

of sacred space, an invasion and plunder of places sacred to demonstrate

ultimate disrespect for what a community holds in the highest respect.

Moreover, its intention is to commit maximum psychic injury and to

reaffirm the devaluation and degradation of all things Black which

a racist culture requires. Therefore, even a shared faith does not

save a Black church from the general racial devaluation of its congregation

and the violent imposition which racist ideology and institutional

arrangements undergird and inspire.

Acts of Terrorism

The burnings also are acts of terrorism directed toward creating

a generalized and palpable sense of communal vulnerability. The terror

of arson seeks to shock and shatter confidence in the central place of

communal sanctuary, to shake and undermine the spiritual ground on which

the community of believers stand. The intention here is to call into

question and even annul the very concept of the Black church as a sanctuary,

a place of refuge, security and protection and to create a communal sense

of apprehension and bewilderment. The latter sense is best expressed

by the recurring questions of the victims, the violated who ask: "how

could anyone do this; who could stop so low and what kind of people would

destroy even God's house?"

Acts of Historical Erasure

Another way of understanding these burnings is to recognize that they

are also acts of historical erasure, attempts to disrupt historical

continuity and memory, and to interrupt the historical rhythm of communal

life. The African American church has historically been a central site

of communal resistance and struggle, of education, culture and spiritual

grounding. It has produced many of the community's leaders and fostered

the concept and practice of communal unity and autonomy. It is here

that Sojourner Truth spoke, Martin Luther King preached, Mary McLeod

Bethune taught, Ella Baker strategized, and the community met and talked

about freedom and justice and forged plans of struggle throughout history.

The church is also the ongoing center of the community life-cycle ceremonies-birth

and baptism, marriage and passing. As this central site of struggle,

autonomy and life-cycle ceremonies, the Black church is a place of

records, a priceless archive of documents, objects, symbols and memory.

Given this, to burn this sacred and meaningful place is to erase history

and create a special sense of horror, outrage, and loss.

Acts of Opportunistic Predation

Finally, the burnings are acts of opportunistic predation. It

is a predatory and cowardly targeting of the most vulnerable, the rurally

isolated, the socially devalued, those without powerful lobbies or numerous

representatives to compel the state to defend them. They are burnings

by those who assume that not only will the congregation not respond in

kind, but that given their devalued and less powerful position in society,

little will be done to catch, punish or prevent the predators.

The Unavoidable Issue of Race

Here we are inevitably brought back to the issue of the racial character

of justice, power, privilege, respect and motivation in this country.

And it is in recognition of this that a series of questions often posed

in statement form, constantly reoccur in the African American community.

To wit: would the burning of 40 white religious institutions-churches,

synagogues or temples-have produced such a low level response from

government and media? Would the victims and violated been investigated

as the primary suspects? Would the FBI, the premier investigative body

of the country wait mysteriously in the wings on such a major and revolting

offense while the Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms group repeatedly wander

through the wreckage discovering nothing and denying the obvious? Would

the President have been so slow in response and act as if photo opportunities

for pastors, and on site visits and pieties about personal sorrow were

enough? And is the country interested in solving one of its most heinous

patterns of crime or in saving face in the world and diminishing talk

of terror so that in Atlanta and elsewhere the games can go on?

Issues of Power, Wealth, and Status

The National Council of Churches, The Christian Coalition and various

Jewish organizations have condemned the burning, offered or given money

and help for rebuilding. But many in the Black community have rightly

seen this as inadequate and in the case of the right-wing Christians,

hypocritical. For it is seen like another version of the old racist

trick of quoting the Constitution and bible in public and whistling

Dixie in the dark. And it also is in stark contradiction to their cloaked

and openly racist positions on other critical social issues. But regardless,

no talk of psychic healing, no money or help given to rebuild churches,

by liberal or right-wing groups can cure the systemic sickness that

inspired the burnings and that assigns its victims unequal worth and

status in society. It is a continuing weakness of liberalism and conservativism

to imagine that the problem is one of attitudes rather than issues

of wealth, power and status. They confuse racial prejudice, an attitude

of hostility and hatred, with racism, a systemic imposition, ideology

and institutional arrangement, which turn attitudes of hatred and hostility

into public policy and practice. And thus this is a problem that can

only be solved by struggle, by a broad movement made up of people of

solid moral courage, integrity and determination, drawing from the

best of our various ethical traditions and dedicated to a thoroughgoing

change in relations of power, wealth and status in this country. And

it is only through such a thrust that we can create a just and good

society and that the outrage, terror and talk of fire around Black

church burning and other violations of human rights and dignity will

become a thing of the past.

The Best of Our Tradition

But regardless of how such a movement develops, anyone who has studied

Black history knows that this episode of violence and violation, no

matter how perverse and painful, cannot undo or dispirit us. We will,

as always, not only survive but prevail. It is a teaching from The

Husia, an ancient sacred text of our ancestors, that we are "given

that which endures in the midst of that which is overthrown," that

this eternal and divine in us "cannot be burned by fire or wet by water," and

that our obligation, regardless of costs, is "to bear witness to truth

and set the scales of justice in their proper place among those who

have no voice, and always do the good." Thus, even as our churches

burn, we have reached inside ourselves and brought forth the strength

to rebuild our institutions and resume our interrupted lives. Even

in the midst of our sorrow, we will, as always, still stand up, clear

away the ashes, lay new foundations, treat our injuries, bury our fallen,

celebrate our births and continue the historic struggle to build the

moral community and world we want to live in. Given the demands of

our history and self-understanding, we cannot and will not do otherwise."

|